Can Restorative Justice Offer the Healing Victims Need?

Restorative justice imagines justice as “repair” to the harm caused by crime

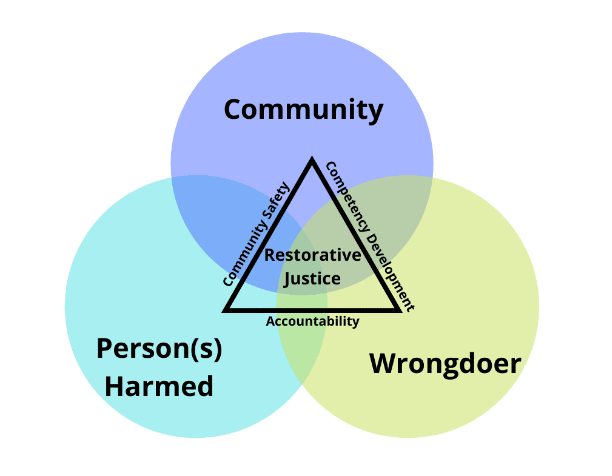

At its core, restorative justice defines “justice” in a radically different way than conventional criminal justice responses. Rather than justice as “punishment,” restorative justice conceives of justice as “repair” to the harm caused by crime and conflict. Understanding and responding to the needs of each involved party and the broader community is central to the collective creation of a just outcome.

There are some common human needs experienced in the wake of crime; needs for safety, understanding, validation, information, apology, and repair. These are needs that so often go completely unmet by our mainstream punitive justice responses, which are concerned primarily with assigning guilt and doling out punishments. By bringing the involved parties together in a safe and voluntary dialogue with well-trained facilitators, restorative justice creates an opportunity for those human needs following crime to be met. It offers a more holistic and humanizing view of what it means to pursue justice.

Of course, restorative justice will not be an appropriate option for all incidents of harm. It is a voluntary process and both the harmed party and responsible party need to engage willingly. Furthermore, it is only effective when the responsible party is taking responsibility. Restorative justice processes should always be guided by well-trained facilitators who first take the time to meet individually with all involved parties and determine that no further harm will be caused by bringing those involved together in dialogue.

Historically, in the United States, restorative justice has primarily been used for minor offenses or juveniles. However, research has shown that restorative justice is more effective for crimes that are considered more severe including felony-level offenses. The impact of this approach is evident in its outcomes including reduced recidivism and increased satisfaction on the part of all involved parties, particularly the harmed party or victim. Because of this positive impact, the use of restorative justice is rapidly expanding in criminal justice systems around the United States and the world.

In a recent issue of Jewish Currents magazine, Associate Editor Mari Cohen detailed her experience as a victim of an August 2021 hit and run in New York City. Her thoughtful essay explores the growing calls for restorative justice efforts to address the harms of traffic violence, and the greater societal issue of locking away harm-doers while failing to consider the context for their actions, and the conditions that would enable them to change their behavior and make amends to their victims.

Excerpts from "After the Hit-and-Run;"

When the van hit my right side, it broke seven ribs and my clavicle and collapsed my lung. Had I been hit slightly higher, I could’ve had brain damage; slightly lower, and the crash could’ve permanently impacted my ability to walk. Instead, with time, the lung sprang back to form, and the bones found each other again, without much fanfare or prodding. The entire affair resulted in the greatest show of community care I’ve ever experienced. Complete strangers comforted me and took pictures of the license plate as the van sped away; my mom dropped everything and flew in to stay by my side for two weeks; my best friend packed my things and brought them to the hospital. For weeks, as my right arm hung limp in its sling and I maneuvered in and out of bed sideways to avoid aggravating the pain in my ribs, friends showed up at my door with home-cooked meals and groceries. Experiencing such kindness from people who acted out of an instinctual desire to help rather than any obligation was life-affirming, invigorating.

Yet this was all set in motion by a radically antisocial act: Someone sped through a red light, plowed into me, and then drove away. It was due only to luck, and not to care, that he didn’t kill me.

Lately, instead of emphasizing the importance of criminal consequences, advocates have begun calling for drivers who hit pedestrians or cyclists to be held accountable through “restorative justice,” a term for an increasingly popular set of practices that eschews a focus on punishment in favor of an emphasis on repair and an effort to meet victims’ needs.

I became interested in these tensions within the traffic safety movement in the months after I was hit. I had realized that I didn’t know what I thought should happen to the driver, whom I will refer to as R. It’s anathema in street safety circles to call a crash an “accident,” since advocates and victims believe the term elides both the structural conditions that make crashes more likely and the responsibility of the drivers who cause them. But habits are hard to break: In conducting interviews for this piece, I frequently found myself saying “my accident” before quickly backtracking: “I mean, my crash.” It does seem to matter that the drivers who cause great harm, while they may be careless, are not setting out to injure or kill someone. In cases like mine, the decision to flee the scene adds an element of cruelty, but I could imagine legitimate—if not exculpatory—reasons why someone might do so. What if they were unable to afford a ticket or legal fees? Undocumented and wary of immigration consequences?

A year and a half after my crash, I started speaking to the people who had built and participated in Circles for Safe Streets, the new restorative justice program for traffic violence in New York City, to learn about its efforts to address serious crashes without resorting to incarceration. Meanwhile, I went looking for the man who hit me. I wanted to know why he did what he did, so I might more easily understand his actions in a social context, rather than as one person’s irreparable cruelty. I wanted to ask him why he drove away.

You can read the full essay "After the Hit-and-Run" at Jewish Currents magazine's website. Jewish Currents is a magazine committed to the rich tradition of thought, activism, and culture of the Jewish left.