Homelessness - The Most Significant Barrier for Re-Entry

The rise of mass incarceration and homelessness in the US are inextricably related

In recent decades, the United States has seen the simultaneous rise of mass incarceration and homelessness. The two crises interact with and worsen one another. Mass incarceration and homelessness are driven by the same structural factors and exacerbate one another in a feedback loop.

People on community supervision face many barriers to housing, putting them at high risk of experiencing homelessness in the months following release. People experiencing homelessness are at heightened risk of criminal justice involvement, including violating the terms of their community supervision. Additionally, many US jurisdictions are criminalizing housing-insecure people for engaging in survival behaviors in public spaces.

In 2018, there were 6.7 million people across the country under some form of correctional control; of these, 2.3 million people were incarcerated in prisons, jails, and other detention centers and 4.5 million adults were on community supervision under probation or parole. Alongside incarceration rates, homelessness rose dramatically in the United States since the 1970’s and 1980’s due to a confluence of factors, including the declining availability of affordable housing, the increase in income inequality, the ongoing deleterious impacts of structural racism on access to intergenerational wealth and housing for Black households, and the rise of mass incarceration.

Housing is arguably the most important element of reentry. Housing is foundational for stability in which to reintegrate and for avoiding further law enforcement contact associated with homelessness. Housing is critical to employment, substance use recovery, and successfully completing parole or probation; factors all critical for reentry.

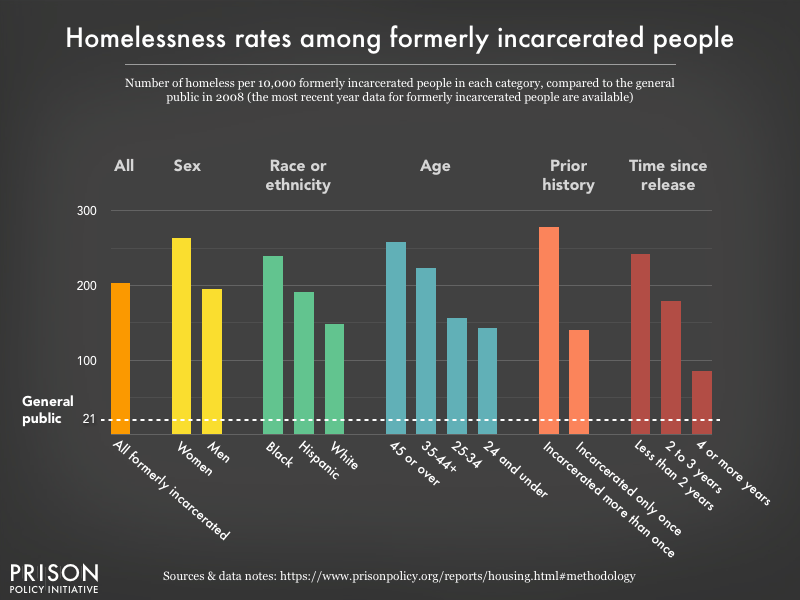

- Formerly incarcerated people in the United States are almost ten times more likely than the general public to experience homelessness - People with more than one incarceration are especially vulnerable to homelessness: those who have one prior incarceration are seven times more likely than the general population to become homeless, while people with multiple prior incarcerations are 13 times more likely to experience homelessness

- Formerly incarcerated people experience high rates of homelessness and housing insecurity, including unsheltered and sheltered homelessness, and reliance on marginal housing like boarding houses, hotels, or motels - For every 10,000 formerly incarcerated people, 570 experience housing insecurity of some kind, as compared to 21 people per 10,000 for the general public. Of the formerly incarcerated people experiencing housing insecurity, 105 per 10,000 are unsheltered (sleeping on the street, in cars, etc.), 98 per 10,000 are living in a shelter, and 367 per 10,000 are marginally housed in a facility like a boarding house, motel, or hotel.

- Homelessness is a risk factor for incarceration and recidivism - Up to 15 percent of people currently incarcerated in prisons and jails were homeless in the year leading up to their incarceration. Relatedly, people are more likely to recidivate (by committing a new crime or violating the conditions of their community supervision) if they do not receive housing and wraparound service support following their release from prison or jail.

- People experiencing homelessness have higher rates of psychiatric and substance use disorders, which contribute to, and are exacerbated by, homelessness - When compared to the general population, homeless populations have higher prevalence of traumatic brain injury, psychosis, depression, personality disorder, drug and/or alcohol dependence, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Unemployment or unstable employment contribute to homelessness, while homelessness is itself a barrier to employment – all of which is worsened by a criminal record or history of incarceration - Formerly incarcerated people experience barriers to employment, including diminished or lost job skills, large gaps in employment history, broken professional networks, and the stigma associated with a criminal record, and thus experience heightened rates of un- and underemployment. Homelessness makes obtaining and maintaining employment even more difficult for formerly incarcerated people by creating new logistical barriers (e.g., lacking a location to shower, a lack of a permanent address for job applications) and placing people in jeopardy of violating their probation or parole for a failure to maintain employment.

Housing, at its core, is a basic human need. We all deserve access to reliable, safe spaces to comfortably shelter and simply live. Leaving prison is often perceived as an opportunity for freedom and redemption, yet the intense state of vulnerability and instability an individual faces upon re-entry hinders such possibilities. Formerly incarcerated individuals must find stable housing and employment to survive.