How Mass Incarceration Punishes Families

In 2023, 57% of the approximately 1.25 million people in state prisons are parents of minor children

Family contact is the most important tool that can help incarcerated people cope with being locked up and reduce their chances of returning to prison. Yet self-reported data from people in state prisons show just how difficult it is to communicate with loved ones, provide financial support even when legally obligated, and make decisions with and about their families. Millions of families and minor children throughout the country are punished emotionally, economically, and otherwise by a loved one’s incarceration.

From the The Bureau of Justice Statistics Survey of Prison Inmates, nearly half (47%) of the approximately 1.25 million people in state prisons are parents of minor children, and about 1 in 5 (19%) of those children is age 4 or younger. Altogether, parents in state prison reported roughly 1.25 million minor children, meaning the number of people in state prison almost exactly mirrors the number of impacted minor children. Research indicates that children of incarcerated parents face formidable cognitive and health-related challenges throughout their development.

The challenges of parenting from prison are particularly likely to affect women. The Survey reveals that women in state prisons are more likely than men to be a parent of a minor child (58% of women, compared to 46% of men). Women were also more likely to have been living with their children prior to their imprisonment: About 52% of women with minor children report living with their child(ren) at the time of their arrest, compared to 40% of men. Finally, women were more likely to lead a single-parent household, as 39% of incarcerated mothers of minors lived with children but no spouse, compared to 21% of fathers.

And like the state prison population overall, incarcerated parents themselves grew up in struggling households:

- 17% spent time in foster care;

- 43% came from families that received public assistance (i.e., welfare) before they turned 18;

- 19% lived in public housing before they turned 18;

- 11% were homeless at some point before age 18; and

- 32% had (or currently have) an incarcerated parent of their own.

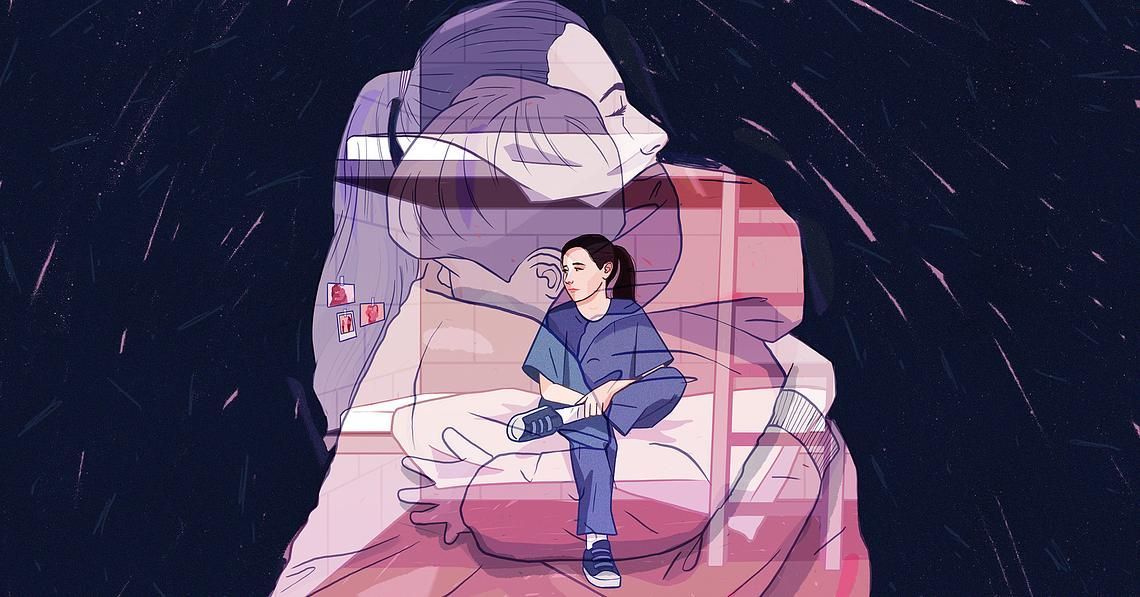

The despair felt by both parent and child amounts to a significant yet largely invisible crisis: the mass punishment of over 1 million children. Short of the parent being released from prison and being offered needed supports, one of the best ways to mitigate these negative impacts is by limiting barriers to meaningful contact between children and incarcerated parents.

Many state carceral policies fail to recognize what so many advocates, researchers, and directly impacted people already know: that state prison incarceration has devastating and far-reaching impacts on family members and entire communities. States and prisons should take steps to ease these burdens, such as making family contact easier through expanded family visitation, visitation assistance, low-cost or free phone calls, and policies that allow real, sentimental mail to be sent from child to parent. What’s more, prisons should ensure that parents are incarcerated as close as possible to their home communities, as in-person visitation may yield some of the most positive impacts on health and behavior.

In the "Life Inside" series, first-person essays from people who live or work in the criminal justice system from The Marshall Project, writer, journalist and activist Maya Schenwar speaks about the difficulties communicating with her incarcerated sister to share the news about her pregnancy.

"I pictured her taking it (a postcard) in her hands during mail call and breaking into an elated grin, yelling to anyone within earshot, “I’m gonna be an aunt!” Each time I saw the prison number flash on my phone and heard the robotic voice asking me whether I’d accept the call, my heart sped up a little. Instead of “Hello,” I answered Keeley’s calls with “Did you get my postcard?” No, she hadn’t — so I sent another, and another. The phone calls stopped due to an extended lockdown at the prison, and five postcards later, I was nine weeks pregnant and no one besides my partner knew.

But the fact that someone threw out five postcards telling Keeley she was going to become an aunt — one of her deepest wishes in life — says something about the everyday cruelty of the system and its casually deliberate acts to deprive people of core human joys, of excitement, of relationship: a survival need."

You can read the full essay, "Motherhood Made Me Even More of a Prison and Police Abolitionist" by Maya Schenwar at The Marshall Project, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization that seeks to create and sustain a sense of national urgency about the U.S. criminal justice system.