On This Date - Furman V. Georgia; Challenging the Death Penalty

Today marks the 50th Anniversary of Furman V. Georgia (1972), where the U.S. Supreme Court declared the death penalty "cruel and unusual punishment," violating the Eighth Amendment

The death penalty has been a part of American legal codes since colonial times, yet despite the longevity of capital punishment, it has never been consistently applied across states. Michigan, for example, abolished the death penalty in 1845. Wisconsin entered the union in 1848 without capital punishment as part of its legal code.

In the late 1960s, the Supreme Court started to more closely examine the way the death penalty was administered. The Court heard two cases in 1968 dealing with the discretion given to the prosecutor and the jury in capital cases. The first case was U.S. v. Jackson, where the Supreme Court heard arguments regarding a provision of the federal kidnapping statute requiring that the death penalty be imposed only upon recommendation of a jury. The Court held that this practice was unconstitutional because it encouraged defendants to waive their right to a jury trial to ensure they would not receive a death sentence. The other 1968 case was Witherspoon v. Illinois, where the Supreme Court held that a potential juror’s mere reservations about the death penalty were insufficient grounds to prevent that person from serving on the jury in a death penalty case. Jurors could be disqualified only if prosecutors could show that the juror’s attitude toward capital punishment would prevent him or her from making an impartial decision about the punishment.

The landmark 1972 Furman v. Georgia case was actually three separate death penalty appeals: Furman v. Georgia, Jackson v. Georgia, and Branch v. Texas. In the first, a 26-year-old man named William Henry Furman was sentenced to death for murdering someone while attempting to burglarize a home. Furman gave two separate accounts of what had happened. In one, the homeowner tried to grab him and shot blindly on his way out. In the other version of events, he tripped over a gun while fleeing, fatally injuring the homeowner by accident. A jury found Furman guilty of murder during the commission of a felony (the burglary). Members of the jury were given the option of death or life imprisonment and chose to sentence Furman to death. In Jackson v. Georgia, Lucius Jackson, Jr. was found guilty of sexual assault and sentenced to death by a Georgia jury. The Georgia Supreme Court affirmed the sentence on appeal. In Branch v. Texas, Elmer Branch was also found guilty of sexual assault and sentenced to death.

Attorneys on behalf of Furman argued that his sentence was “a rare, random and arbitrary infliction” of punishment, not allowed under the Eighth Amendment. Specifically in the Furman case, that he had been sentenced to death yet there were conflicting reports of his “mental soundness” was particularly cruel and unusual. The attorneys further pointed out that the death penalty was used more frequently against poor people and people of color. The jury that convicted Furman knew only that the victim died by a shot from a handgun and that the defendant was young and Black.

By a vote of 5 to 4, the Court held that Georgia’s death penalty statute, which gave the jury complete sentencing discretion, could result in arbitrary sentencing. The Court held that the scheme of punishment under the statute was therefore “cruel and unusual” and violated the Eighth Amendment. From Justice Thurgood Marshall's concurrence:

"It is the poor, and the members of minority groups who are least able to voice their complaints against capital punishment. Their impotence leaves them victims of a sanction that the wealthier, better-represented, just-as-guilty person can escape. So long as the capital sanction is used only against the forlorn, easily forgotten members of society, legislators are content to maintain the status quo, because change would draw attention to the problem and concern might develop. Ignorance is perpetuated and apathy soon becomes its mate, and we have today's situation…"

Furman v. Georgia halted executions nationally. Between 1968 and 1976, no executions took place in the U.S. as states scrambled to comply with the Court’s ruling in Furman. Once the decision was handed down, it seemed as if it would abolish the death penalty altogether by complicating the procedural requirements. By 1976 however, 35 states had shifted their policies in order to comply and resumed applying the death penalty.

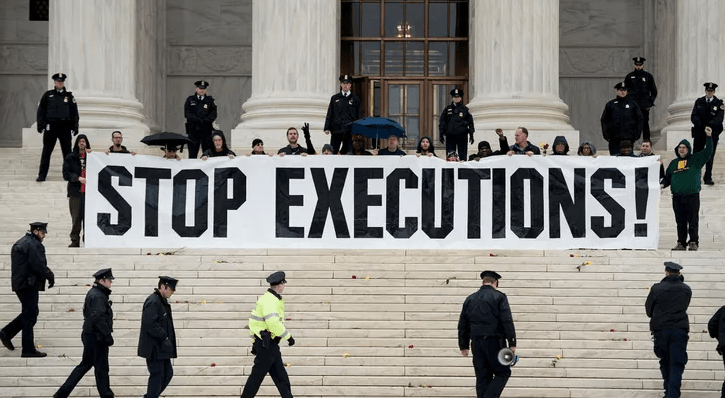

As of today, 24 states still allow the death penalty. 23 states have abolished it altogether, and three states, California, Oregon, and Pennsylvania, have governor-issued moratoriums in place and halting executions. 50 years after the landmark Furman v. Georgia ruling, the issue remains contentious, as the arbitrary nature of the application of death penalty sentences Justice Marshall noted in his concurrence still very much exists.