Report - US Out of Step Globally with Felony Disenfranchisement

Four million Americans were unable to vote in 2024 election due to felony disenfranchisement laws

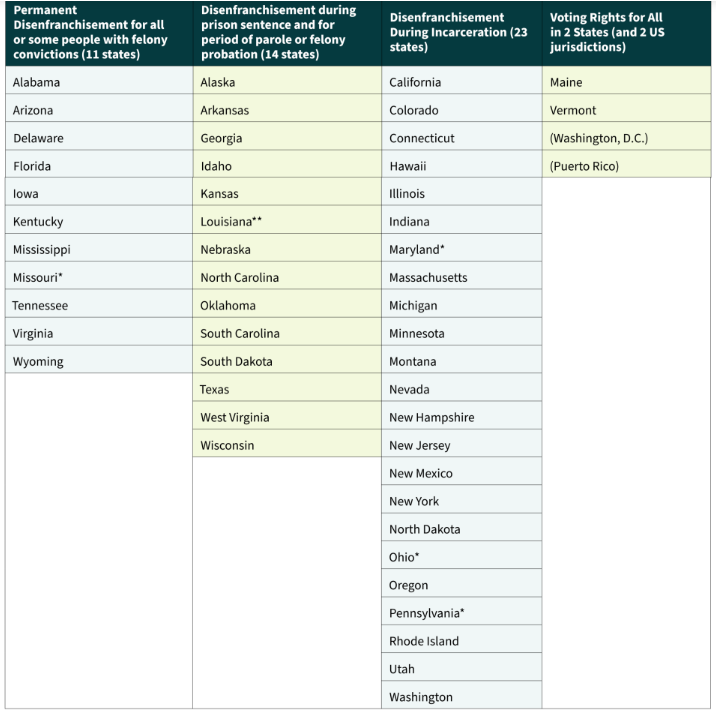

Millions of Americans are excluded from our democratic process on the basis of criminal disenfranchisement laws. These laws strip voting rights from people with past criminal convictions, and they vary widely between states. Twenty-five states bar community members from voting, simply on the basis of convictions in their past.

Felony voting bans keep communities that have been historically unheard and under-resourced from having equal representation in our democracy.

Political participation and equal treatment are widely recognized as universal human rights. These rights are codified by international and regional human rights agreements that the United States has ratified. Despite these obligations, felon disenfranchisement laws in 48 states contradict the US pledge to “universal and equal suffrage.” Furthermore, the disproportionate impact of these policies on African Americans breaches guarantees to nondiscrimination as a human right.

State felony disenfranchisement laws arose during the post-Civil War era, when the Reconstruction Act of 1867 affirmed universal suffrage for all men.

“At that point, two interconnected trends combined to make disenfranchisement a major obstacle for newly enfranchised Black voters,” according to a 2017 report from the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. “First, lawmakers — especially in the South — implemented a slew of criminal laws designed to target Black citizens. And nearly simultaneously, many states enacted broad disenfranchisement laws that revoked voting rights from anyone convicted of any felony.”

A recent report from The Sentencing Project notes how the United States still lags behind most of the world in protecting the right to vote for people with criminal convictions; people who have a great deal to contribute to the health of a democracy. Incarcerated citizens have intimate knowledge of the criminal justice system that prison officials, staff and outside citizens don’t, and we fail to take advantage of their direct experience to shape policy when we do not take their vote into consideration.

Restoring the right to vote for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people could also reduce recidivism rates. Fifty-four percent of citizens impacted by incarceration believe that voting would help them stay out of federal and state prisons and local jails after their internment. Participating in society by feeling included in developing laws would help released prisoners, making them less likely to break society’s laws. After Chicago’s Cook County Jail established a polling location in 2019, the jail saw a 40 percent turnout in the 2020 general election.

“In all seriousness, what better way [is there] to get a person committed to their community?” Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart said. “They’re voting for the people that are running their community.”

You can read the full report, "Out of Step: U.S. Policy on Voting Rights in Global Perspective" at The Sentencing Project.