Solitary Watch - When Freedom Still Feels Like Prison

Since 2015, the United Nations has regarded solitary confinement for more than 15 days as a form of torture.

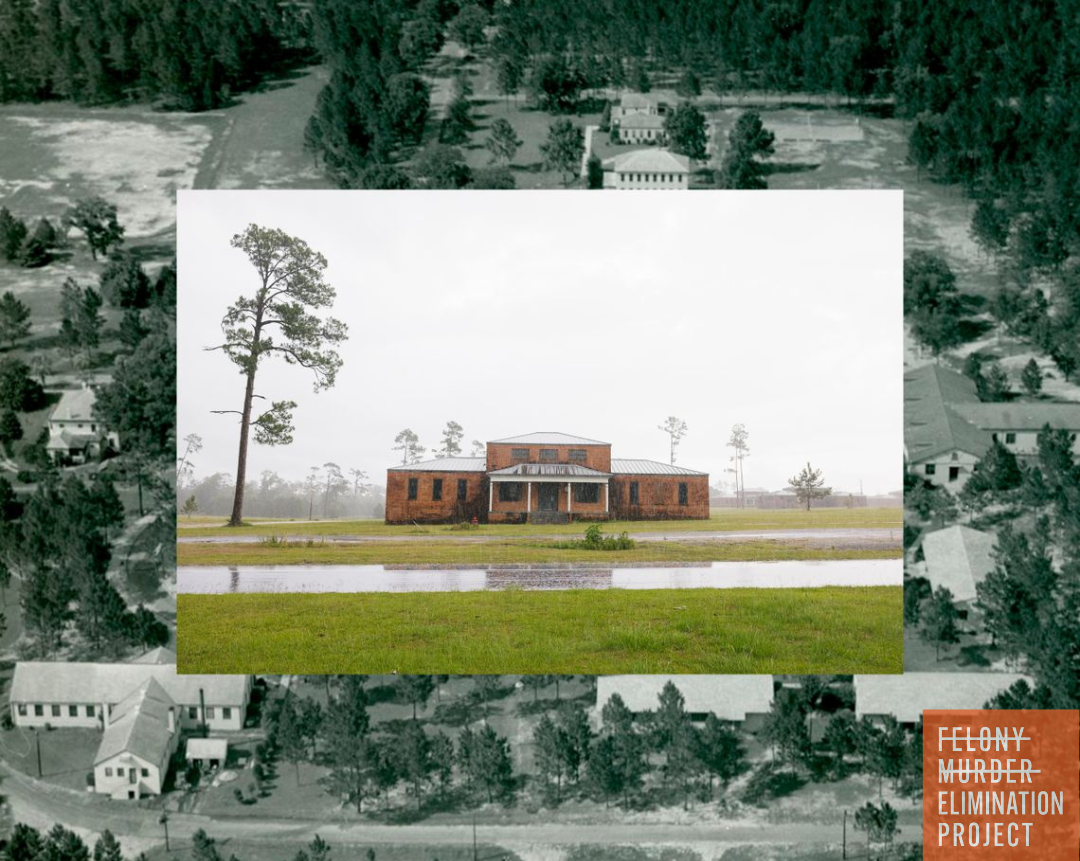

Some form of short-term isolation from the rest of the prison population is used almost everywhere as punishment for breaches of prison discipline. However, many states use solitary confinement more routinely and for longer periods of time. In the United States, it is estimated that 80,000-100,000 individuals are being held in some form of isolation.

Medical research strongly indicates the denial of meaningful human contact can cause ‘isolation syndrome’, the symptoms of which include anxiety, depression, anger, cognitive disturbances, perceptual distortions, paranoia, psychosis, self-harm and suicide. Prolonged isolation can destroy a person’s personality and their mental health and its effects may last long after the end of the period of segregation.

Use of prolonged and extended solitary confinement also increases the risk of torture or ill-treatment going unnoticed and undetected, and it can in itself constitute torture and ill-treatment, in particular where it is prolonged or indefinite.

Of note:

- Contrary to popular belief, solitary confinement is not reserved only for the most dangerous prisoners. Often it is imposed to isolate detainees during the pre-trial stage of investigation, including as part of coercive interrogation. It is also used to lock away incarcerated persons with, or who are perceived to have, mental illnesses.

- Many countries use prolonged periods of solitary confinement or semi-isolation for those serving a life sentence, often separating them from the rest of the prison population for the entirety of their sentence. In countries still using the death penalty, and in those where it was only recently abolished, death row prisoners are also typically held in strict solitary confinement.

- In his report to the UN General Assembly in 2011, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture recommended a ban on prolonged or indefinite solitary confinement as a punishment or extortion technique. Such treatment runs contrary to the prohibition on torture and other ill-treatment and is a ‘harsh’ measure, undermining the goals of rehabilitation, the primary aim of a criminal justice system.

Despite this, the routine use of solitary confinement is growing and is becoming more and more common in high-security and supermax prisons designed to hold incarcerated people who are deemed high-risk or difficult to control.

Solitary Watch recently interviewed 21 formerly incarcerated people who are members of the National Network of Solitary Survivors, a landing point and community for survivors of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons and jails that is providing peer support and collegiality to people who have faced isolated confinement first-hand, as they described their needs and shared their personal struggles for help.

Quotes from the interviews are included below.

“When you first get out you’re happy to be free, you enjoy inhaling air that’s not in a concrete bunker. But soon,” all the difficult feelings hit you, the ones you’d been stuffing down while in the SHU.” - Prisoner 19, anonymously identified as a plaintiff in 2015 class-action lawsuit against the state of California that was settled in 2015.

“The anxiety that I would feel—and that I still feel sometimes—and just trying to be around people”—especially in public spaces—was “incredibly difficult to deal with. I isolated a lot.” - Deuce, who spent three years of 22 total incarcerated in solitary confinement in Virginia.

“I was extremely excited because I was getting out of prison. But I was also very scared. I was alone. I was confused.” - Natasha White, formerly incarcerated after serving 15 years in New York State prisons.

You can read part one of these interviews, "When Freedom Still Feels Like Prison," at the Solitary Watch website. Solitary Watch is a nonprofit watchdog organization that works to uncover the truth about solitary confinement and other harsh prison conditions in the United States by producing high-quality investigative journalism, accurate information, and authentic storytelling from both sides of prison walls.