Terminally Ill Persons Remain in North Carolina Prisons Despite Reforms

Costs of incarceration skyrocketing as people sentenced to long prison terms in the 90's are now aging and in need of complex medical care

One of the least discussed results of mass incarceration is the number of older adult prisoners who, as a result of receiving life without parole sentences (LWOP) earlier in life, have aged while incarcerated. There are a significant number of older adult individuals serving LWOP sentences; a 2022 Sentencing Project study indicated nearly a quarter of all LWOP prisoners are over the age of 65 and nearly half are over 50. Even more alarming is that incarcerated individuals experience an increased rate of aging as a result of prison conditions, meaning that someone in prison has the equivalent health of someone 10 to 15 years older in the outside world.

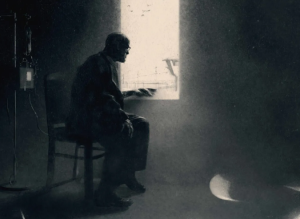

Older adult prisoners are also much more susceptible to illness, something that is further exacerbated by poor prison healthcare. Prisons are, in many ways, not built for people living with neurocognitive conditions like dementia, as the typical correctional setting relies on a person understanding, remembering, and learning rules and tasks that are difficult or impossible for a person with neurocognitive deficits. In theory, there is a solution: compassionate release programs. These programs and policy reforms are designed to release prisoners with terminal illnesses or those who are extremely advanced in age.

There is substantial evidence that states persons eligible for compassionate release programs pose little to no threat to community safety. In a 2017 report, the Vera Institute found that recidivism research demonstrates that arrest rates drop to just more than 2 percent in people ages 50 to 65 years old and to almost zero percent for those older than 65. Releasing older adult prisoners poses a very low danger to communities overall, and in cases of prisoners with debilitating health problems, many are unable to commit new crimes.

Compassionate release is not only important for the safety and well-being of the released older adult prisoners, it can also significantly reduce state spending. A report written by the ACLU estimates that releasing an aging prisoner will save states, on average, $66,294 per year per prisoner, including healthcare, other public benefits, parole, and any housing costs or tax revenue. Even on the low end, states will save at least $28,362 per year per released aging prisoner.

Considering the number of prisoners over the age of 65, states could save a substantial sum of money by better utilizing compassionate release. The money saved by allowing prisoners to die in their own communities could be used to fund rehabilitation programs and reduce recidivism in younger prisoners.

In North Carolina, where 17% of the incarcerated population is age 55 or older, reforms were introduced to reduce the cost of prison health care. In a bi-partisan effort, the GOP-led state legislature made changes to the state's compassionate release guidelines in 2023, and Democratic Governor Roy Cooper signed the changes into law.

Yet North Carolina's compassionate release program benefits a small fraction of incarcerated people who could truly benefit from the program due to stringent eligibility guidelines. Sandra Hardee, Secretary of NC-CURE (Citizens United for Restorative Effectiveness), a non-profit advocating against all forms of inhumane treatment of incarcerated people, believes that there are still barriers to actually releasing terminally ill people who qualify.

“Right now, there are about 1,000 people that could be qualified by age and crime,” Hardee said. “If they were released, it would be a step in the right direction, but there is no way to identify them.”

You can read more about North Carolina's compassionate release guidelines and accounts of incarcerated persons who could benefit from the program in "Terminally Ill People Languish in North Carolina Prisons, Even After Reforms" from Bolts Magazine, a news organization reporting on local elections and obscure institutions that shape public policy but are dangerously overlooked in the U.S., and the grassroots movements that are targeting them.