Book Bans in Prison - Which Stories Are Being Told?

Loosely-defined policies vary state to state; Florida bans 20,000 books, Rhode Island 68

As book banning is all the rage in some parts of the United States, the journalists at The Marshall Project asked every state prison system for book policies and lists of banned publications. About half of the states said they kept such lists, which contained more than 54,000 titles. As with a lot of data that comes out of prisons, there were problems. One state didn’t respond to records requests at all. A handful sent unusable, messy data. About half of states, as well as the Federal Bureau of Prisons, said they don’t keep lists.

Authorities in many states often evaluate each publication as it comes in, meaning that a book rejected at one prison may be permitted at another, or a book that is banned one month could be allowed in the next. The procedures in states which do have banned books lists often start when the mailroom staff at one prison flag an incoming book (often ordered online by a prisoner’s friends or family members), then refer it to a review committee or a higher-ranking official to decide whether it should be prohibited statewide.

The resulting lists vary widely. While Florida bans more than 20,000 titles and Texas bans nearly 10,000, Rhode Island prohibits just 68. Nebraska maintains a list for only one of its nine prisons, while Wyoming has a different list for each facility. In total, more than 54,000 books are banned behind bars.

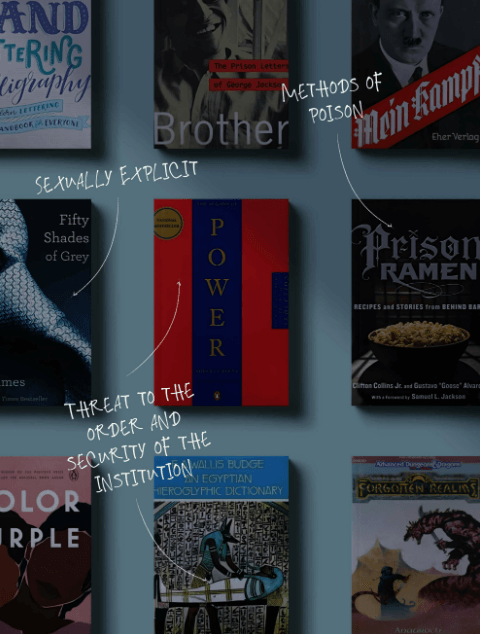

When Marshall Project staff started looking through all the prohibited titles, the first thing they noticed was that prison systems where lots of books are banned are not generally safer or less chaotic than those that don’t ban many titles. Maybe that’s in part because of the second thing noticed: many of the justifications for the bans were absurd. Some states deemed Dungeons & Dragons books a security “threat,” while others banned many yoga books and anatomy texts over “explicit” illustrations.

“I have heard of very few book bans that actually seemed logical at any point in history,” said Keramet Reiter, a law professor at the University of California Irvine. Virginia prisons ban her book, “23/7: Pelican Bay Prison and The Rise of Long Term Solitary Confinement,” because the state said it promotes violence or criminal activity. “The idea that a book from a top university press about the history of prisons would be banned is surprising,” Reiter said. “What is so disturbing about the history of these institutions that the people running them feel like it can’t be told?”

Many states also banned books over content relating to violence or fighting, even though prisoners already have access to legal paperwork and court filings describing violent crimes in detail. So while incarcerated people can go to the law library to read about rapes and murders, in Virginia they cannot have World of Warcraft books, and in Texas, they cannot own books about Tai Chi, a form of martial art known for slow, meditative movements.

Undoubtedly more troubling than the books that are banned are those that are not. Of the states that sent lists, only seven explicitly banned “Mein Kampf,” while only four banned “The Turner Diaries,” a 1976 extremist text about exterminating people who aren’t white. While Texas prisoners can read Hitler’s manifesto, the state banned pioneering Black journalist Ida B. Wells’ book “On Lynchings” because its examination of racist vigilante mobs used “racial slurs.” Similarly, Louisiana bans texts by Black prison abolitionists, including George Jackson’s “Blood in My Eye” and Mariame Kaba’s “We Do This ‘Til We Free Us” for being “racially inflammatory.” Yet "Mein Kampf" is allowed, as well as every single book mentioned in the Southern Poverty Law Center’s round-up of racist literature.

You can view the updated list "The Books Banned in Your State Prisons" at The Marshall Project's website.