Death & Redemption in an American Prison - NPR

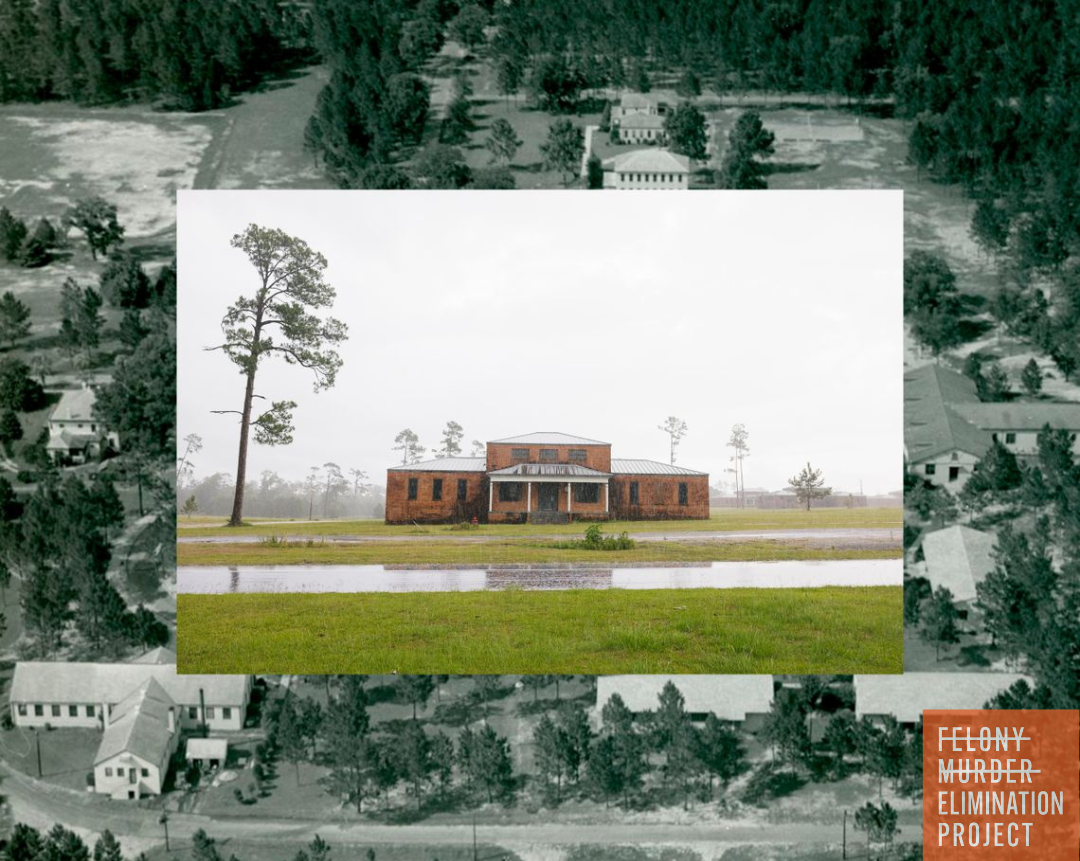

Dubbed "America's Bloodiest Prison," the first-in-the-nation prison hospice program spreads peace instead of sowing conflict

The following piece, "Death and Redemption in an American Prison" by Markian Hawryluk, appeared on the National Public Radio website on February 19th, 2024 and features the hospice program at Louisiana State Penitentiary (known as Angola), the first prison hospice program in the country. Excerpts from the piece are featured below.

*****

Steven Garner doesn't like to talk about the day that changed his life. A New Orleans barroom altercation in 1990 escalated to the point where Garner, then 18, and his younger brother Glenn shot and killed another man. The Garners claimed self-defense, but a jury found them guilty of second-degree murder. They were sentenced to life in prison without parole. When Garner entered the gates at Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, Louisiana, he didn't know what to expect. The maximum security facility has been dubbed "America's Bloodiest Prison" and its brutal conditions have made headlines for decades.

It wasn't until five years later that Garner would get his chance to show everyone he wasn't the hardened criminal they thought he was. When the prison warden, Burl Cain, decided to start the nation's first prison hospice program, Garner volunteered. In helping dying inmates, Garner believed he could claw back some meaning to the life he had nearly squandered in the heat of the moment. For the next 25 years, he cared for his fellow inmates, prisoners in need of help and compassion at the end of their lives.

The Angola program started by Cain, with the help of Garner and others, has since become a model. Today at least 75 of the more than 1,200 state and federal penal institutions nationwide have implemented formal hospice programs. Yet as America's prison population ages, more inmates are dying behind bars of natural causes and few prisons have been able to replicate Angola's approach.

The primary rule of the hospice program was that no one would die alone. When death was imminent, the hospice volunteers conducted a vigil round-the-clock. The program used medications, including opioids, for the palliative care of patients, though the inmate volunteers were not allowed to administer them.

The first hospice patient Garner saw die was a man the prisoners called Baby. Standing just 4-foot-5, he was sought out by other inmates for his self-taught legal expertise. In 1998, as Baby was dying from cirrhosis, a disease of the liver, inmates rushed in to get his advice one last time. "So many people wanted to see him, we just didn't have enough room to take everybody in," Garner said. "We used to have to do increments of 10 guys or whatever."

Baby had taken care of everybody else. Now it was their time to take care of him.

Most of the hospice volunteers were serving life sentences, and many, like Garner, had taken someone's life to get there. But holding a man's hand as he took his last breath provided a new perspective. "You become their hands, you become their eyes, you become their feet, you become their thinking sometimes," Garner said. "They're so vulnerable to where you actually have to be so mindful and careful to carry out their will."

In a place where people prey on weakness, hospice volunteers shared in each patient's vulnerability. Instead of assaulting, they assisted. Instead of sowing conflict, they spread peace.

*****

You can read the full feature "Death and Redemption in an American Prison" at the NPR website.