Ending the School-to-Prison Pipeline; Reconsider Police in School

More police in schools results in more suspensions and expulsions

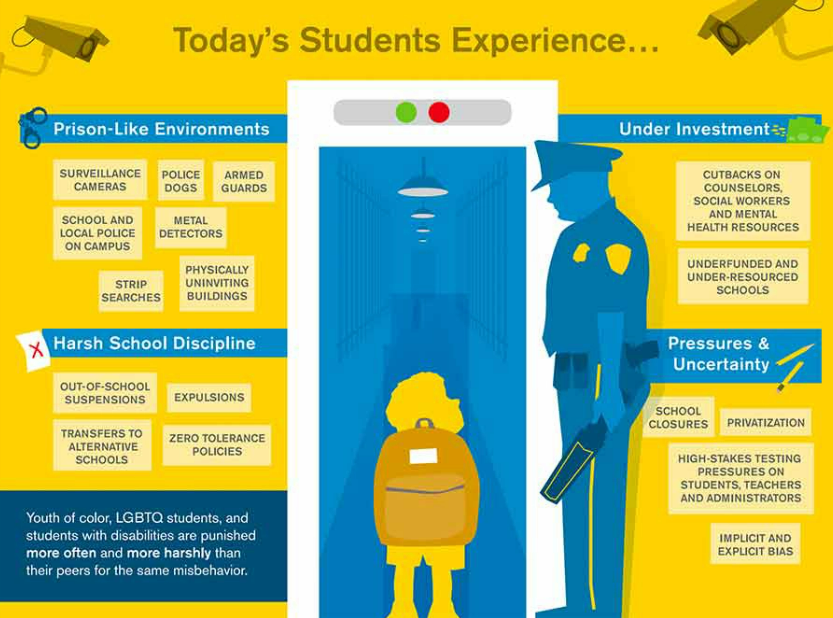

Although white education systems have criminalized Black and brown youth in many different ways throughout our social history, the roots of the modern school-to-prison pipeline are often traced to the "zero-tolerance" educational policies passed in the 1990s hysteria around "Super predators" that demonized a whole generation of youth of color amid a larger wave of tough-on-crime laws. Suspensions and expulsions exploded over the following decades, and so did school police: Between 1975 and 2017, the number of public schools in the U.S. with police stationed on-site or regularly patrolling the campus increased from 10 percent to more than 60 percent. With police came a rise in arrest as a form of school discipline.

Suspension, expulsion, and arrest all fall under the umbrella of “exclusionary discipline.” These sorts of responses increase the likelihood that students will fall behind, drop out, or wind up in the criminal legal system, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Exclusionary discipline has not been meted out equally; during the 2017-2018 school year, Black students were suspended and expelled at more than five times the rate of white students. Arrest rates for Black students are comparable in most years. Black students with disabilities are typically disciplined even more disproportionately. Other students of color face similar disparities.

These trends mean that Black and brown students are often criminalized for doing things that historically have landed kids in detention, not handcuffs. Rather than preventing crime, school police officers have been linked with increased arrests for noncriminal, youthful behavior, fueling the school-to-prison pipeline.

Since 2020, amid the outcry over racist policing and violence following the murder of George Floyd, at least 50 school districts have ended contracts with police departments. Some have implemented alternatives like the “restorative justice coordinators” now on staff in Madison, Wisconsin, public schools. Some large school districts, including those in Los Angeles and Chicago, haven’t cut police out of the equation entirely, but have significantly downsized policing and redirected funding toward more supportive methods of addressing students’ behavioral needs.

The initial outcomes at schools that have eliminated police could encourage others to follow suit. Schools in Portland, Maine, are operating normally after removing police, and in Minneapolis, public schools have seen fewer disciplinary measures since replacing police with "unarmed public safety support specialists."

For a review of policing in schools and effective proposals focus on public safety in schools, read "A Better Path Forward for Criminal Justice: Reconsider Policing in Schools" from The Brookings Institution.