Nearly 70 Bills Seek To Restore Voting After Felony Conviction

Felony disenfranchisement laws have well-known racist origins since 1870

Since the 2020 election, a surge of legislation restricting voting access has moved through state legislatures. In 2023, anti-voting bills remain a fixture in Republican states across the country. Yet, there is one voting policy area where proposed legislation has been overwhelmingly positive: improving felony disenfranchisement laws to restore voting rights to formerly incarcerated individuals.

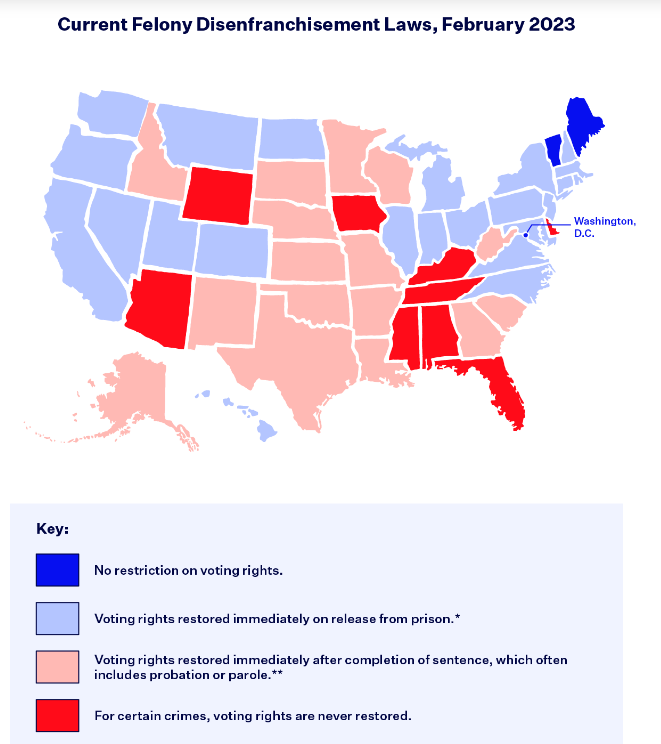

As of the end of February 2023, at least 73 bills related to felony disenfranchisement have been introduced in over 20 states. Of these 73 bills, 68 of them ease existing felony disenfranchisement laws to differing extents. The remaining five bills look to make the laws more restrictive, which means that 93% of bills related to voting rights in the criminal legal system move in the pro-voting direction, a stark comparison to other policies governing voting access.

Felony disenfranchisement laws have a well-known racist origin, adopted soon after Black men were granted the right to vote in 1870. At the same time that states enacted felony disenfranchisement laws, lawmakers expanded legal codes that over-incarcerated African Americans. Since then, explosive prison and jail population growth — increasing by over 500% over the past 50 years — means that 2% of the voting-age population in the United States is excluded from political participation.

A 2003 study found that states with larger nonwhite prison populations are more likely to adopt the strictest of felony disenfranchisement laws. Today, in eight states — Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Dakota, Tennessee and Virginia — 10% of Black adults are disenfranchised.

Minnesota has already succeeded in creating and passing legislation that will restore voting rights for people with felony convictions once they leave prison, and the successful passage was the result of years of advocacy by community groups. “I’m a spouse, a husband, a proud father of a 14-year-old daughter. And like some of you, I’m a businessman, a homeowner…I am a leader in my community,” a formerly incarcerated Minnesotan testified at a January hearing about Minnesota’s bill. “But unlike you I don’t have a voice. Unlike you, I’ve been made to feel like a second class American, because I can’t vote.”

To read more about the states moving legislation to end felony disenfranchisement, as well as the states seeking to add further restrictions, read the article

"Nearly 70 Bills Introduced To Restore Voting Rights After Felony Conviction" at the

Democracy Docket, an organization dedicated to providing information, analysis and opinion about voting rights, elections and democracy.