Recruiting Alone Doesn't Solve Prison Staffing Crisis

Raises, added benefits, and new facilities haven't turned recruitment around

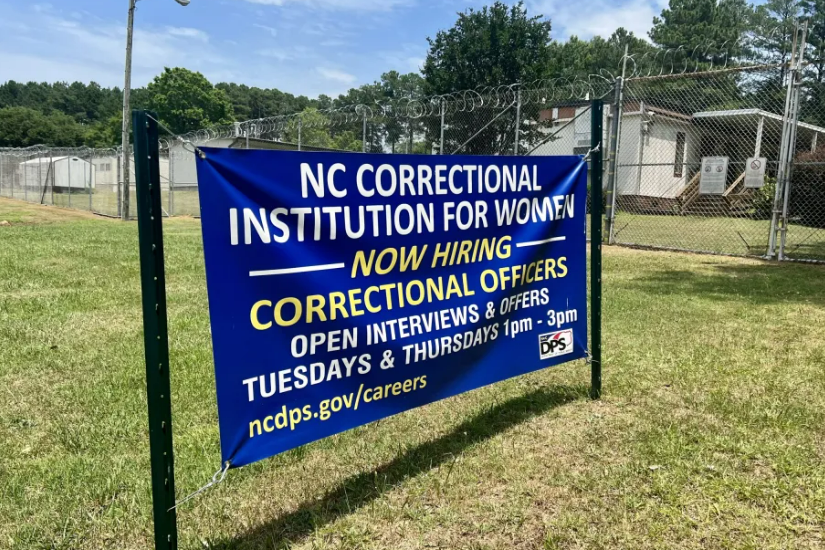

Prisons across the country have long struggled to recruit and retain staff, but the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows the situation is particularly dire.

The number of people behind bars steadily declined starting in 2013 and then drastically dropped during the COVID- 19 pandemic, when states released people to ease dangerous COVID-19 conditions and court systems slowed. But by 2022, the number of people held in state prisons started to bounce back to over 1 million people, and the number of people working for state prisons hit its lowest mark in over two decades. This number doesn't just represent correctional officers, but also cooks, plumbers, teachers, and healthcare workers.

Conditions created by too few prison workers can lead to more violence. Locked in their cells for long stretches, people are more likely to act out against staff and fellow prisoners. Short staffing in Mississippi has contributed to assaults against officers. In Nevada, a union for correctional officers blamed the murder of an incarcerated person on low staffing. The dynamic creates a spiral, where poor conditions make prison employees quit, which then leads to worse conditions, causing more staff to leave.

Localities have tried ramping up hiring and staffing levels, increasing pay and benefits, yet understaffing and resulting problems persist. But corrections workers say that pay alone is not enough to retain staff if prisons also neglect fixing the poor working conditions that lead to officers quitting: mandated overtime, poor mental health support and violence.

Terrica Redfield Ganzy, executive director of the Southern Center for Human Rights, sued the Georgia Department of Corrections in 2021 over poor prison conditions. She said the state needlessly incarcerates people for technical parole violations, even as it faces a major staffing crisis. Ganzy also argues the state could release more elderly and sick prisoners without risking public safety.

“One of the things that I think people are starting to agree on now is that we're not likely in the … foreseeable future to be able to fully staff. We're incarcerating people at a high rate, and the staffing numbers are just not keeping up,” Ganzy said.

Nearly every single solution to the prison understaffng crisis adds to the problem and creates the cyclical spiral mentioned above. Few, if any, look at the biggest factor; mass incarceration.

A recent report from Prison Policy Initiative examines why raises, benefits, and new facilities haven't turned recruitment around, and what that informs about the state of mass incarceration.

- Staffing is down despite annual wage growth

- Recruitment strategies can’t address fundamental problems in jails and prisons

- Pay increases, easing employment requirements, staff wellness programs, new facility construction, and other desperate measures haven't worked

- Decarceration is the most straightforward, workable solution to the problems for which “understaffing” is blamed.

Read the full report, "Why Jails and Prisons Can’t Recruit Their Way Out of the Understaffing Crisis" from

Prison Policy Initiative, a non-profit organization that

produces cutting edge research to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization, and then sparks advocacy campaigns to create a more just society.