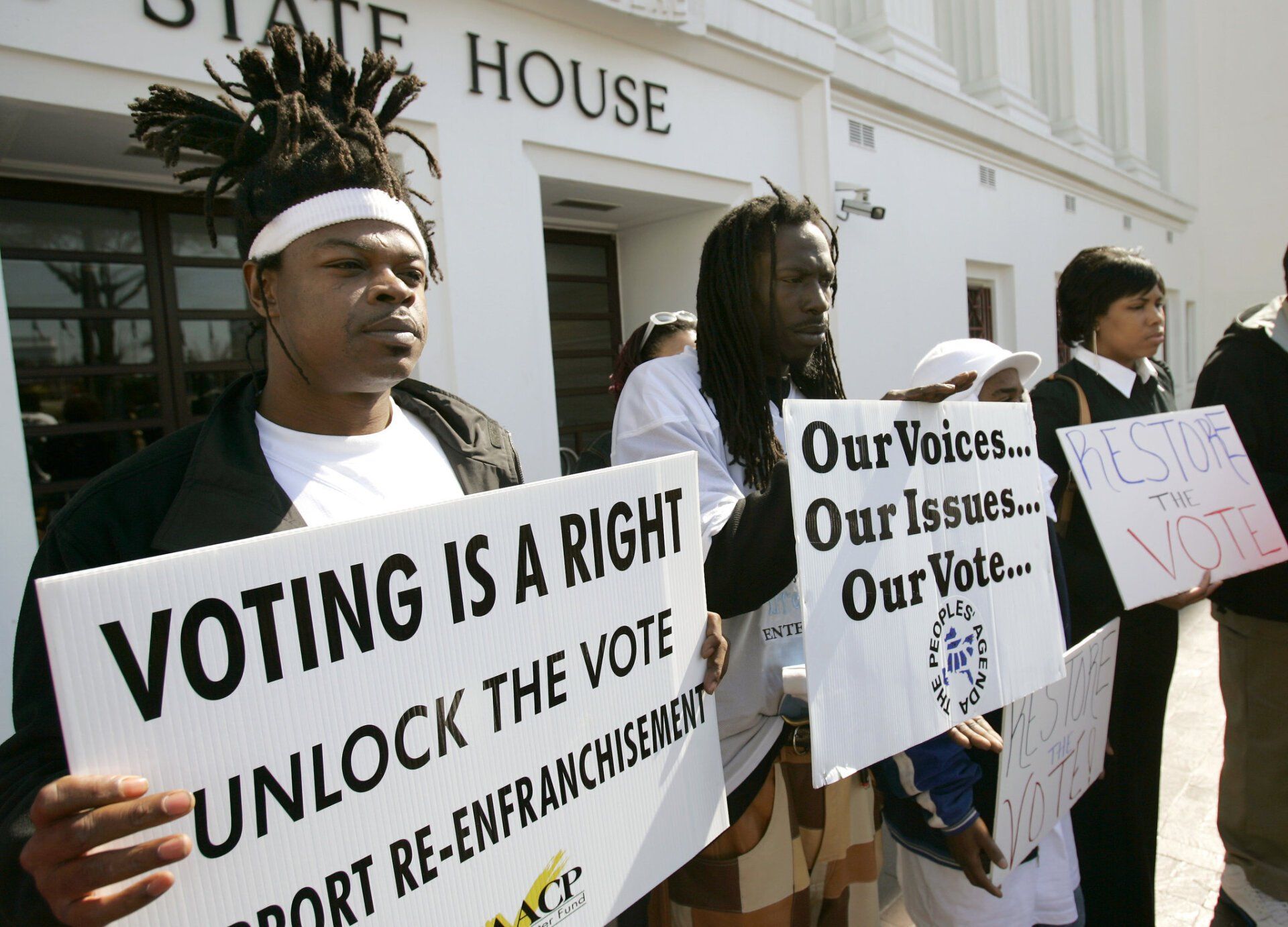

The State of Felony Voting Disenfranchisement

Denial of voting rights has a disproportionate impact on communities of color

A record-breaking number of Americans voted in the 2020 election, reflecting the electorate-at-large's desire to have their voices heard and prioritize the issues most important to them and their communities. The primary election scheduled for Tuesday November 8th is shaping up to be as important in addressing issues, both in local, "dinner table" policies, and for the larger overall state of democracy itself in the United States.

However, multiple states silenced 5.2 million voices in 2020 due to their current or prior interactions with the criminal legal system. All but two states, Maine and Vermont, as well as Washington, DC and Puerto Rico, in some way restrict people with a felony conviction from voting while in prison, on parole or probation, or post-sentence. These voices being silenced are disproportionately Black and brown as a result of the overcriminalization of these communities.

The arguments supporting felony disenfranchisement are contrary to the ideals of a democratic society and are steeped in racism and discrimination. Restricting the right to vote is not only undemocratic but also counter to the research and benefits, as studies show many opportunities come to communities and individuals when the right to vote is available.

The 11 most extreme states (Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nebraska, Tennessee, Virginia, Wyoming) restrict voting rights for some or all individuals even after they have served their prison sentence and are no longer on probation or parole. These individuals make up more than half - 58 percent - of the entire disenfranchised population.

In Florida, voters passed a 2018 amendment that restored the voting rights of most people who had completed their sentences. In response to the voice of the people, Florida state legislators in 2019 made restoration conditional on a repayment of all restitution, fines, and fees. Therefore, only people who have paid all legal financial obligations have become eligible to vote, resulting in almost 900,000 people who owe legal financial obligations remaining disenfranchised in the state due to Florida's updated version of a Jim Crow poll tax. Three other states (Alabama, Arizona, and Tennessee) also require repayment of legal financial obligations in order to having constitutionally-protected voting rights restored.

Recent public opinion surveys indicate that a majority of the Americans identifying with both major political parties favor restoring voting rights to persons who have completed their sentences. Public awareness brought to the issue resulted in reform at the state level, from legislative changes expanding voting rights to grassroots voter registration initiatives targeting individuals with felony convictions.

Some recent examples:

- In 2020, Washington, DC became the first jurisdiction in the country to restore voting rights for people in prison

- Ten states either repealed or amended lifetime disenfranchisement laws since 1997

- Ten states have expanded voting rights to some or all persons on probation and/or parole since 1997

- Sixteen states and Washington, DC enacted voting rights reforms between 2016 and 2021, either through legislation or executive action

Research lends credence to the idea that restoring voting rights to those with experience in the criminal justice system helps their transition back into the community, and that failing to restore those rights upon release furthers a sense of isolation from the community, despite the positive link between community participation and lower rates of recidivism. In one study of persons who had previous arrest records, 27% of non-voters re-offended, compared to 12% of voters. With continued study, it becomes clearer that restoring voting rights is an important part of the package of pro-social behaviors that strongly links successful community reintegration for released persons.

You can download this PDF of "Voting Rights in the Era of Mass Incarceration" from the Sentencing Project.