Politics Win Over Humanization in South Carolina Prisons

"Restoring Promise" program at Lee Correctional Institution stymied by state politics

Between 2013 and 2019, researchers from the Brennan Center for Justice organized four such study trips to introduce American criminal justice officials to several different Northern European corrections systems. During a November 2018 visit to the neat and well-appointed living and working quarters of Halden Prison in southern Norway, researchers had the opportunity to see the maximum security facility that has received much international attention for being the “most humane prison in the world.”

The delegation was surprised not only by the physical aspects of the place — open, well-lit, and bright, with lots of green spaces — but also the high degree to which the conditions of confinement were organized around the normalization principle, which recognizes the inherent harms of incarceration and requires that life in prison approximate the positive aspects of life in the community. Under this principle, punishment is restricted to the separation from society mandated by the custodial sentence itself. Conditions of confinement should themselves be neither punitive nor onerous. Instead, the aim of the incarceration experience is to enable smooth reintegration of people upon release and to lead a life of social responsibility.

Halden is organized around the promotion of safety, well-being, and personal development, orchestrated to mimic life on the outside. Incarcerated individuals live in private rooms with doors and private bathrooms. Small groups share communal living spaces that include fully equipped kitchens. They are also encouraged to maintain a healthy measure of autonomy and personal agency in organizing their daily lives — they cook their own meals and are provided with an array of vocational training and educational programs, as well as various treatment options. They are given ample opportunities to maintain contact with family and friends, and they can all earn the award of brief periods of temporary leave from prison.

Contrast this with the U.S. corrections system, where penal life and settings are ordered around the paramount goals of “custody and order.” American prison life is built upon the dehumanizing rituals of induction, initiation, hierarchy, degradation and routine, all designed to assert authority and control over the bodies and lives of incarcerated people. Individuality is stripped away upon prison entry, replaced by an inmate number and a standardized, nondescript uniform.

Recidivism rates make this contrast between punitive vs. rehabilitative philosophies even more stark. European prison systems tend to prioritize rehabilitation and reintegration into society, offering programs to address the root causes of crime and support offenders after release. The U.S. criminal justice system is often criticized for prioritizing punishment over rehabilitation, which is a significant factor leading to higher recidivism rates. A 2019 study from Eastern Kentucky University found that recidivism rates in the United States (70%) are almost triple that of most European countries (20% in Norway).

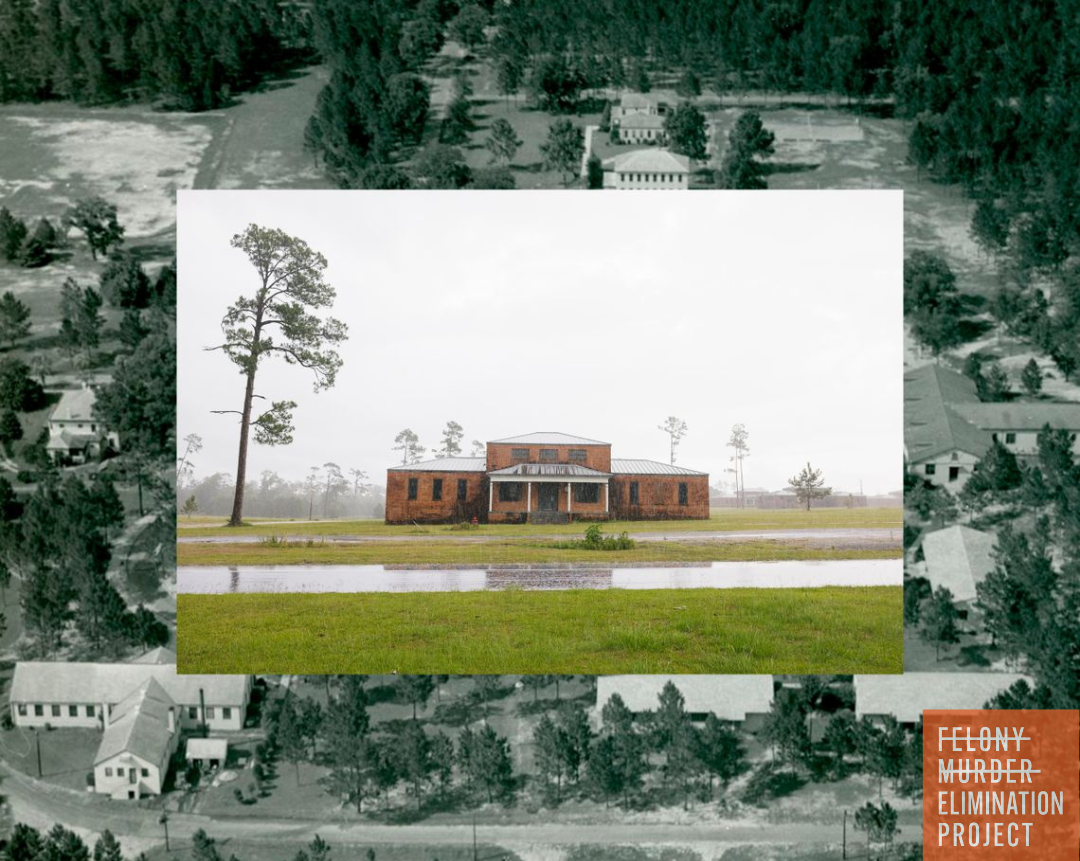

An investigative feature from The Marshall Project followed attempts at the Lee Correctional Facility in Bishopville, South Carolina, to institute the Restoring Promise program. This program, modeled after rehabilitative corrections approaches in Europe, was an initiative of the Vera Institute of Justice that seeks to transform prison cultures, climates, and spaces by partnering with correctional leaders to reimagine housing units for young adults and realign corrections policies and practices with a commitment to human dignity.

At Lee Correctional, what started out as a promising initiative that found success in states like Connecticut, Massachusetts, Colorado and North Dakota was soon beset by political pressure and inaction. Some former corrections department leaders described a series of setbacks. They asked the state to pay the mentors, and were denied. Governor Henry McMaster (R) allowed the Restoring Promise units to take root, but he and the South Carolina state legislature focused most of its political capital on limiting early prison releases and restarting executions.

To read more about the Restoring Promise program and the political roadblocks encountered, you can read "The Future of Prisons?" at The Marshall Project. The Marshall Project is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization that seeks to create and sustain a sense of national urgency about the U.S. criminal justice system.